| |

Every culture across the globe has its ghost stories, some are intended as parables of a sort to teach a lesson to the listener, some are merely entertainments to produce a frisson of fright just as a joke is supposed to prompt a laugh, and others purport to be true, be they on the level of urban myths or genuine tales of strange things that went bump in the night once upon a time. All three kinds have been captured by writers down the years, and Japanese ghost stories are no different: the four selected for the 1964 film Kwaidan were drawn from the work of ex-pat writer Lafcadio Hearn who moved to Japan and collected yarns like these.

Though a Westerner, Hearn was accepted into the Land of the Rising Sun thanks to his obvious respect for and fascination with Japanese culture, and decades later director Masaki Kobayashi helmed his own adaptations of four of them for Kwaidan, though he was not largely known for his horror movies. Indeed, it's debatable whether this was categorised as a horror back in the mid-nineteen-sixties as it was regarded as something far classier than the likes of what Hammer or A.I.P. were churning out around this period, generating much appreciation from the cognoscenti who proclaimed Kobayashi's efforts a masterpiece.

It's probably no coincidence that a key character in nineties cult favourite The Usual Suspects is called Kobayashi, a hark back to the director who had woven his own magic with storytelling in a film that was explicitly about the art of the story, even featuring a writer as a character by the end. And what better subject matter to examine this with than the ghost story, one of the purest expressions of the form? The opener chosen for Kwaidan was Black Hair, a motif familiar from many Japanese horrors: the ghost of the woman with the long, straight, black hair hanging over her face as she advances on the terrified victim. It's probably no coincidence that a key character in nineties cult favourite The Usual Suspects is called Kobayashi, a hark back to the director who had woven his own magic with storytelling in a film that was explicitly about the art of the story, even featuring a writer as a character by the end. And what better subject matter to examine this with than the ghost story, one of the purest expressions of the form? The opener chosen for Kwaidan was Black Hair, a motif familiar from many Japanese horrors: the ghost of the woman with the long, straight, black hair hanging over her face as she advances on the terrified victim.

You would see it in the Japanese horror boom of the turn of the millennium, where Ring and The Grudge ruled the Eastern roost when it came to putting the wind up audiences, even remade and sequelised in countries that previously would rarely have considered adapting Japanese themes and imagery as part of popular fiction. Black Hair has a samurai who has abandoned his doting first wife to increase his social standing and marrying a nobleman's daughter who is cold and aloof; when he realises the error of his ways, he returns home to his original spouse and finds the home derelict, but she does still live there after all these years.

Well, "live" is pushing it, and that was a thing about the stories in Kwaidan: until we reached the last one, which for various reasons existed to confound, the other three tales were almost perversely predictable, as if Kobayashi was instructing you to examine the structure and effect of them rather than be swept up in anything as obvious as being caught out by a twist, like a conventional movie would do. This was especially noticeable in the second, Woman of the Snow, and not merely because it would be familiar to some from its remake in the nineties horror anthology out of America, Tales from the Darkside.

It took the character of a woodcutter who gets lost in a blizzard in the forest, who meets and is saved by a female spirit who tells him he must never share this account with anyone else, or else it will be his ruination. He solemnly agrees and goes on to settle down and have a family, but will he be able to keep his secret with his beloved? If you can't tell that at the point where the spirit makes him swear not to say anything, then maybe Kwaidan would operate on that basic level of storytelling, yet everything about it said its director was aiming higher than that, turning over the concepts and folk tales in his mind.

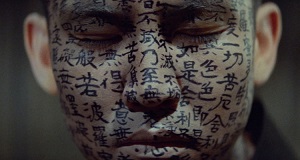

For one thing, the film looked absolutely beautiful, be that the eyes in the sky above the snowy wilderness or the stylised battle scene that opens the third tale, with the ooh what a giveaway title of Hoichi the Earless - it's almost as if Kobayashi just didn't care about tradition in the very technique he was performing. It told of the title character (who starts out with ears, anyway) who is a blind biwa player with an extensive knowledge of story songs (of course) who becomes an unwilling part of the history of the battle he is an expert in when he is contacted by the ghosts of the battle's dead to play for them. For one thing, the film looked absolutely beautiful, be that the eyes in the sky above the snowy wilderness or the stylised battle scene that opens the third tale, with the ooh what a giveaway title of Hoichi the Earless - it's almost as if Kobayashi just didn't care about tradition in the very technique he was performing. It told of the title character (who starts out with ears, anyway) who is a blind biwa player with an extensive knowledge of story songs (of course) who becomes an unwilling part of the history of the battle he is an expert in when he is contacted by the ghosts of the battle's dead to play for them.

This was the longest episode of the lot, and the most digressive as it hared off on tangents of comedy and spirituality before returning to the point, which was how Hoichi became known as "The Earless", which is at once a bit of sick comedy and something truly horrible and painful. For that finale, we had a story without a conclusion, since that is a form they can take as well, for many motives and explanations, none of which were related here as Kobayashi preferred to leave everything up in the air. It was about a military man who sees a reflection in his cup of tea - but the reflection is not his own!

This was designed to have the film stick in your mind, for what else will a story without a denouement do but have you ponder how it was meant to close? If Kwaidan verged on the academic, which despite its international success back in the sixties it seemed to appeal more to a specialist audience, then its succession of striking visuals would guarantee people returned to its strange, rarefied air time and again. On Eureka's Blu-ray, you can appreciate the film as intended, fully uncut (the Woman in the Snow section was often excised early in the production's life abroad) and with the colours popping off the screen. The special features are as follows:

• Hardbound Slipcase

• 1080p presentation on Blu-ray from Criterion's 2K digital restoration of Kobayashi's original director's cut

• Original monaural Japanese soundtrack

• Optional English subtitles

• Kim Newman on Kwaidan - a new interview with the film critic and writer

• Shadowings [35 mins] - a new video essay by David Cairns and Fiona Watson

• Original trailers

• PLUS 100-PAGE Perfect Bound Illustrated Collector's book featuring reprints of Lafcadio Hearn's original ghost stories; a survey of the life and career of Masaki Kobayashi by Linda Hoaglund; and a wide ranging interview with the film maker - the last he'd ever give.

|